I’ve been trying to get my head around what the actual day-to-day nursing of a dysentery patient would have looked like – and the relationship between the nurses at the Casualty Clearing Stations with the bacteriologists. What the nurses understood of the bacteriology, their relationship to the process of diagnosis etc etc.

I’ve been reading an article by a guy called Robert Atenstaedt about the development of bacteriology (full citation below). He talks about the British going into the Crimean War with such a tiny, unprepared medical team (old soldiers who couldn't carry themselves let alone patients). It was the first war after Telegraph was invented, and the immediacy of the news about soldiers suffering (from dysentery amongst other things) generated outrage at home. That outrage drove the creation of the medical corps. It makes me think of learning about Vietnam, the televised war. It also puts Florence Nightingale in context.

He goes on to say that, despite new knowledge, bacteriologists in WW1 were considered low status - it was routine water testing. Anyone with medical training was wanted for what was felt to be more important work. So it makes sense that Sister Williams was able to carve a niche for herself as a bacteriologist.

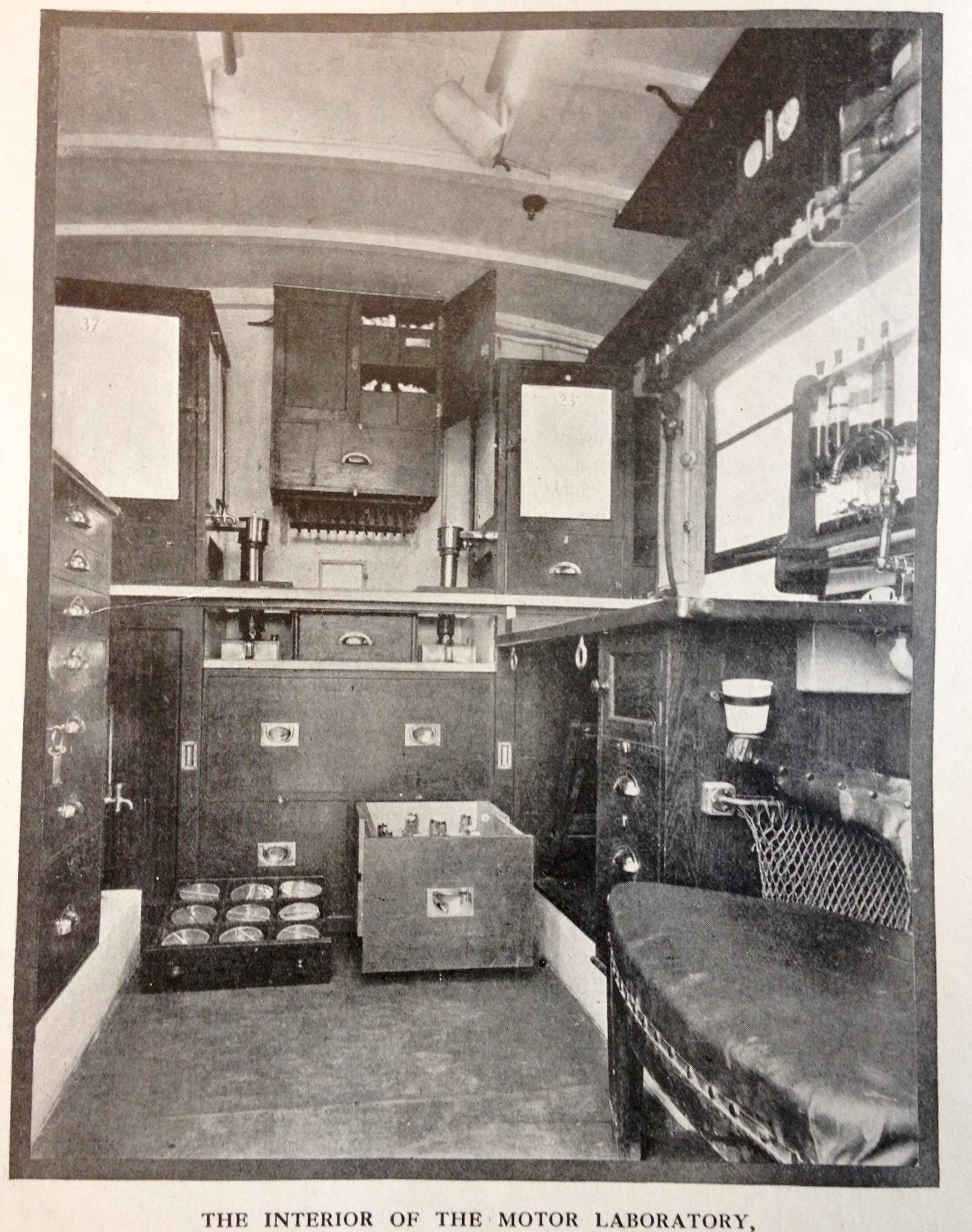

Briony, seeking the Wellcome Library online catalogue has found the Mobile Laboratory. We were scanning through a whole screen of thumbnails and suddenly it was there. This image, I nearly squealed.

Atenstaedt describes the first one, quoting :

a motor vehicle was fitted out with all the pathology paraphernalia of the day including microscopes, centrifuges, autoclaves and incubators: 'The inside of this multum-in-parvo thing on wheels was equipped with everything that the heart of a bacteriologist would require’

(if you’re wondering what multum-in-parvo means, it’s ‘much in little” - ie. the old school way of saying ‘tardis’).

He says there were 15 mobile laboratories built, and each had a two-seater cycle car for collecting specimens. I love the two-seater cycle car. It’s our physical link between the nurses and the laboratory. It's the pathway the samples take.

A woman called Rachel at the British Royal College of Nursing helped me out, showing my how to search their archive. British Journal of Nursing has some fabulous articles about the treatment of dysentery. Some highlights:

A SEVERE CASE OF DYSENTERY (Dec 1915)

The feeding of the patient from October 22nd to 26th consisted of small quantities of albumin water, egg-flip, jelly, brandy, and champagne, given every two hours

and

WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF DYSENTERY, AND HOW IS IT TREATED? (a prize winning paper by Miss Bessie Grey Johnson 1917)

The patient should be kept warm in bed, and should use the bedpan for all evacuations... If there is not too much tenesmus, rectal injections of either of the following solutions, as prescribed, warmed to 100' F., should be allowed to run slowly into the bowel from a funnel through a long soft tube :- Boric acid, I drachm to I pint. Nitrate of silver, 5 or 10grains to I pint. Quinine, 10grains to I pint.

I read these aloud to Gregory and Briony who gasp and giggle and at one point Gregory muttered, “Pure witchcraft”.

Another prize winning article is all my heart desires: WHAT PRECAUTIONS WOULD YOU TAKE IN SAVING FOR MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION, A SPECIMEN OF URINE, A SPECIMEN OF SPUTUM, A SPECIMEN OF FAECES?

I still have a lot of questions. I want to know who drove the cycle car? Who ordered the specimens? Where did the nurses store them? How far did the mobile laboratories travel? And who emptied the bedpans...

Atenstaedt article details:

"The Development of Bacteriology, Sanitation Science and Allied Research in the British Army 1850-1918: Equipping the RAMC for War by RL Atenstaedt (JR Army Med Corps 156 (3): 154-158)