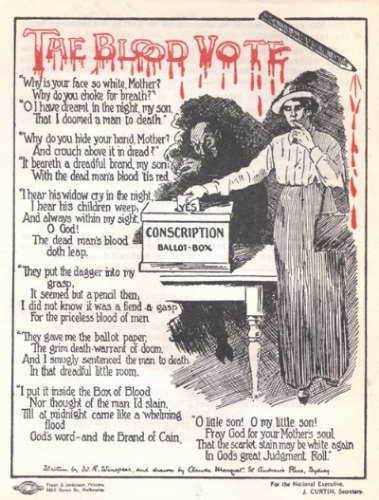

I’m reading What’s Wrong with Anzac? Part of what they are saying seems to be that Australians promote an idea that our nation was shaped by that conflict, by those months in Gallipoli, but that actually this country was also shaped by the peace movement. That this is an important part of our history to keep telling. I remember reading about the Australian conscription referendums when I was in high school. I remember my little modern history class and the sense of pride we all had that our country had voted no. That every soldier in Australia who went, had the choice. That the soldiers at the front voted no. I remember reading the classic “Blood Vote” poem and analysing it to learn about propaganda and emotive language.

One of the nurse’s journals I’m reading – Olive Haynes, makes a note when the results of the referendum comes in. She is furious and heartbroken. Our brave boys fighting in such awful conditions while the shirkers sit at home. They should be forced to come. She’s tending these broken men every day and sending letters home to the mothers of those who died. She thinks they deserve all the support their countrymen can give. “Our boys say they only voted no because they didn’t want to ask for help.”

My great grandfather, Herbert Dobbing

My great-grandfather was a conscientious objector in the UK. He was imprisoned as a traitor with all kinds of other criminals for the duration of the war. The story I heard as a child was that the conscientious objector “traitors” were actually on their way to the front on a train, to be sent over the top first without weapons. Someone on that train wrote a note and threw it out the window and it made it to the newspapers. There was an uproar. So the objectors were brought back and imprisoned instead. Whether this story is true I don’t know, but it’s a powerful one for a seven year old to form an identity around. That my great grandfather was not prepared to kill for his beliefs, but he would have died for them.

I’ve been reading Regeneration by Pat Barker. Siegfried Sassoon in his internal moral battle. An officer whose men loved him, who fought bravely and was tactically hugely successful. Who didn’t believe that war was wrong, but who came to believe that this war was wrong. My favourite story about Sassoon is that he singlehandedly took a German trench, scattering 60 German soldiers, and then instead of letting command know that he’d done it, he sat down and read poetry for two hours. The British gained no tactical advantage from his skills and bravery that day.

I don’t imagine there will be room in this book we're writing for a debate about conscientious objection, the peace movement and the political reasons for war, or Australia’s involvement. But perhaps it would work for the story to have conversations about the conscription debate – which was so divisive in this country and people had such strong opinions about. I also have a vision of one soldier patient with his bandaged foot in the air being in the corner of every page. Saying nothing, but one day reading Sassoon’s “Declaration of a Soldier” and the next Bertrand Russell etc etc. So the ideas are pointed to, but don’t make part of the main text.