We spend hours reading the books we have, trawling the internet for more articles, writing to librarians and archivists, reading out moments of gold, explaining the new information we've found. We're working everywhere, out in the garden, over lunch dinner, over coffee, in the car on the way to the next battlefield.

We gather round the table to map out timelines and sometimes find it difficult to hear each other, the scientist to the artist to the writer. We are absorbed, frustrated, irritated, astonished, overwhelmed. We curl up after dinner to watch ANZAC Girls and All Quiet On the Western Front and comment on locations, gas masks, medical equipment, make verbal notes of what we need to look up tomorrow.

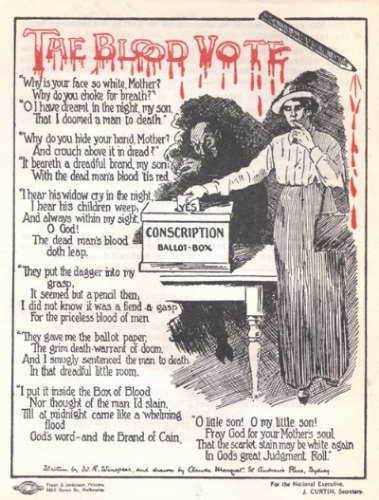

I take the war poets to bed and read Owen, Sassoon, Rosenberg, Gurney blinking to sleep over the pages.

Briony emailing museum archives in the 'jardin'

Gregory demonstrating the movement of phages through mucus, with the assistance of three chopsticks and a prawn cracker, over dinner at Fuji Yama